Movies Home / Entertainment Channel / Bullz-Eye Home

It's been called by many names – The Big Apple, The City That Never Sleeps and The Capital of the World – but one thing New York City most certainly is not, is the City of Love. Nevertheless, that hasn't stopped directors like Woody Allen, Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee from falling in love with the city again and again over the course of their careers. The producers of "Paris, je t'aime" have clearly taken notice, because they've chosen the City So Nice They Named It Twice as the backdrop for their latest compilation of short films about that thing people in Little Italy call "amore."

In conjunction with the release of their new film, "New York, I Love You," Bullz-Eye staffers sat down to discuss our favorite New York-based movies. What we discovered is that it's virtually impossible to put together a definitive list, so in an attempt to make it a little easier on us, we limited the number of films per director to one. As expected, it only made our final list even more well balanced; these aren't just movies that take place in New York, but ones in which the city is practically a character itself.

King Kong (1933)

King Kong (1933)

Crazed filmmaker/explorer Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong) would have been better off if he had thought more like the female theatergoer who, after being told that King Kong is a gorilla of some sort, asks logically, "Ain't we got enough of them in New York?" Less than a third of Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack's original monster masterpiece actually takes place in New York – and none of it was shot there – but its most enduring images are as entwined with the mythology of Manhattan as any in filmdom. Special effects master Willis O'Brien terrified depression-era audiences as Kong broke free from his Broadway captivity, destroyed subway trains, randomly bit unfortunate men to death, and not at all randomly picked up poor Ann Darrow (Fay Wray), who found herself traveling up the Empire State Building in an uncomfortably hairy paw. It might be entirely fantasy, but "King Kong" is a real New York movie. Its fake Manhattan is an art deco beauty, and there's something about a giant monster attack that is the most sincere kind of cinematic tribute for any city (just ask Tokyo). Kong's final rampage is the ultimate NYC spectacular. "Holy Mackerel, what a show!"

Crazed filmmaker/explorer Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong) would have been better off if he had thought more like the female theatergoer who, after being told that King Kong is a gorilla of some sort, asks logically, "Ain't we got enough of them in New York?" Less than a third of Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack's original monster masterpiece actually takes place in New York – and none of it was shot there – but its most enduring images are as entwined with the mythology of Manhattan as any in filmdom. Special effects master Willis O'Brien terrified depression-era audiences as Kong broke free from his Broadway captivity, destroyed subway trains, randomly bit unfortunate men to death, and not at all randomly picked up poor Ann Darrow (Fay Wray), who found herself traveling up the Empire State Building in an uncomfortably hairy paw. It might be entirely fantasy, but "King Kong" is a real New York movie. Its fake Manhattan is an art deco beauty, and there's something about a giant monster attack that is the most sincere kind of cinematic tribute for any city (just ask Tokyo). Kong's final rampage is the ultimate NYC spectacular. "Holy Mackerel, what a show!"

On the Town (1949)

On the Town (1949)

"New York, New York a helluva town" became "New York, New York, a wonderful town" in the film version of the trendsetting Broadway musical comedy about three Navy sailors on shore leave. Some changes, like dropping most of Leonard Bernstein's original score, might seem odd now, but movies are different than stage plays. One adjustment that absolutely worked was the use of real Manhattan locations during the groundbreaking opening sequence. Stars Frank Sinatra, Jules Munshin and Gene Kelly (directing and choreographing his first film in partnership with 24-year-old Stanley Donen) cavort near the real Rockefeller Plaza, Central Park and the Statue of Liberty with joyful brio in what remains one of the most famed musical sequences ever filmed. The balance of "On the Town" was actually shot at the MGM lot some 3,000 miles west – but every scene retains a complete supply of NYC feeling. From the stylish, character-specific fashions of leading ladies Vera-Ellen, Ann Miller and Betty Garrett, to the snappy Betty Comden/Adolph Green dialogue and brilliant recreations of subways and the roof of the Empire State Building, this musical is 100 percent New York, even if it's mostly via Culver City soundstages.

"New York, New York a helluva town" became "New York, New York, a wonderful town" in the film version of the trendsetting Broadway musical comedy about three Navy sailors on shore leave. Some changes, like dropping most of Leonard Bernstein's original score, might seem odd now, but movies are different than stage plays. One adjustment that absolutely worked was the use of real Manhattan locations during the groundbreaking opening sequence. Stars Frank Sinatra, Jules Munshin and Gene Kelly (directing and choreographing his first film in partnership with 24-year-old Stanley Donen) cavort near the real Rockefeller Plaza, Central Park and the Statue of Liberty with joyful brio in what remains one of the most famed musical sequences ever filmed. The balance of "On the Town" was actually shot at the MGM lot some 3,000 miles west – but every scene retains a complete supply of NYC feeling. From the stylish, character-specific fashions of leading ladies Vera-Ellen, Ann Miller and Betty Garrett, to the snappy Betty Comden/Adolph Green dialogue and brilliant recreations of subways and the roof of the Empire State Building, this musical is 100 percent New York, even if it's mostly via Culver City soundstages.

Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961)

Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961)

There's something deeply melancholy about Audrey Hepburn as professional party girl Holly Golightly having her pastry and coffee, gazing at a certain world-famous jewelry store at the strangely deserted corner of 5th Avenue and 57th Street. Perhaps it's that we know, even if she can afford to shop there someday, it couldn't possibly make her happy. And that moment sets the tone for the rest of this winsome blend of romanticism, comedy and sometimes brutal pathos – badly marred by Mickey Rooney's ethnically offensive, annoying and completely unfunny turn as Golightly's bucktoothed Japanese upstairs neighbor, Mr. Yunioshi. "Breakfast at Tiffany's" survives this monumentally horrific piece of casting partly because of a strong screenplay by George Axelrod, working from a story by Truman Capote, the evergreen allure of its lithesome female lead, and the poignant mood established by director Blake Edwards. The eye-filling depiction of Manhattan's higher priced and more beautiful venues, including some gorgeous views of Central Park, underlines the feeling of young hopefuls dependent on the whims of wealthier people for their livelihood. Like Holly at Tiffany's, they can enjoy gazing at the city all they like, but they may never be able to buy their way in.

There's something deeply melancholy about Audrey Hepburn as professional party girl Holly Golightly having her pastry and coffee, gazing at a certain world-famous jewelry store at the strangely deserted corner of 5th Avenue and 57th Street. Perhaps it's that we know, even if she can afford to shop there someday, it couldn't possibly make her happy. And that moment sets the tone for the rest of this winsome blend of romanticism, comedy and sometimes brutal pathos – badly marred by Mickey Rooney's ethnically offensive, annoying and completely unfunny turn as Golightly's bucktoothed Japanese upstairs neighbor, Mr. Yunioshi. "Breakfast at Tiffany's" survives this monumentally horrific piece of casting partly because of a strong screenplay by George Axelrod, working from a story by Truman Capote, the evergreen allure of its lithesome female lead, and the poignant mood established by director Blake Edwards. The eye-filling depiction of Manhattan's higher priced and more beautiful venues, including some gorgeous views of Central Park, underlines the feeling of young hopefuls dependent on the whims of wealthier people for their livelihood. Like Holly at Tiffany's, they can enjoy gazing at the city all they like, but they may never be able to buy their way in.

West Side Story (1961)

West Side Story (1961)

The work of two of NYC's most famed resident geniuses, composer Leonard Bernstein and choreographer Jerome Robbins, mostly didn't survive the transition from stage to film in "On the Town," but the film version of their epic, modern-day musical "Romeo and Juliet" was a different story. Bernstein's music filled the film and Robbins co-directed it with veteran helmer Robert Wise ("The Day the Earth Stood Still"). The results were magnificent and 100 percent New York City – even if, once again, only part of the film was actually shot in the city. Certainly the oft-parodied opening ballet/skirmish between the warring Puerto Rican-American Sharks and the Anglo Jets, filmed on real New York streets and schoolyards, is one of the most exciting opening musical sequences ever made. For the balance of the film, production designer Boris Levin's sets present a richly poignant view of working class mid-century Manhattan, right down to the graffiti-style end credits. Even the pointed dialogue, courtesy of Arthur Laurent's original book and the screenplay by Ernest Lehman ("Sweet Smell of Success"), carries the flavor of New York life with all the simmering ethnic tensions, buoyant cynicism, and dark undercurrents that befits a tragic fairytale of New York.

The work of two of NYC's most famed resident geniuses, composer Leonard Bernstein and choreographer Jerome Robbins, mostly didn't survive the transition from stage to film in "On the Town," but the film version of their epic, modern-day musical "Romeo and Juliet" was a different story. Bernstein's music filled the film and Robbins co-directed it with veteran helmer Robert Wise ("The Day the Earth Stood Still"). The results were magnificent and 100 percent New York City – even if, once again, only part of the film was actually shot in the city. Certainly the oft-parodied opening ballet/skirmish between the warring Puerto Rican-American Sharks and the Anglo Jets, filmed on real New York streets and schoolyards, is one of the most exciting opening musical sequences ever made. For the balance of the film, production designer Boris Levin's sets present a richly poignant view of working class mid-century Manhattan, right down to the graffiti-style end credits. Even the pointed dialogue, courtesy of Arthur Laurent's original book and the screenplay by Ernest Lehman ("Sweet Smell of Success"), carries the flavor of New York life with all the simmering ethnic tensions, buoyant cynicism, and dark undercurrents that befits a tragic fairytale of New York.

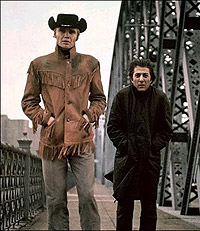

Midnight Cowboy (1969)

Midnight Cowboy (1969)

Frank Sinatra told us that if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere – but what Frank didn't tell us about New York was that you can go there to make your small-town dreams come true, only to end up sleeping in an abandoned building and turning tricks with dudes for spare change. Yes, the Big Apple can be a cruel mistress, as discovered by Joe Buck (a never-more-innocent-looking Jon Voight) discovered in 1969s unremittingly bleak "Midnight Cowboy." This is a vision of the city devoid of real happiness; even something as simple as going to a party is rewarded with a trip down a flight of stairs. And if you try to escape New York? Heck, just ask Ratso Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman) what happens. Oh, that's right, you can't ask him; he died on the bus during his long dreamed-for trip to Miami. Start spreading the news!

Frank Sinatra told us that if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere – but what Frank didn't tell us about New York was that you can go there to make your small-town dreams come true, only to end up sleeping in an abandoned building and turning tricks with dudes for spare change. Yes, the Big Apple can be a cruel mistress, as discovered by Joe Buck (a never-more-innocent-looking Jon Voight) discovered in 1969s unremittingly bleak "Midnight Cowboy." This is a vision of the city devoid of real happiness; even something as simple as going to a party is rewarded with a trip down a flight of stairs. And if you try to escape New York? Heck, just ask Ratso Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman) what happens. Oh, that's right, you can't ask him; he died on the bus during his long dreamed-for trip to Miami. Start spreading the news!

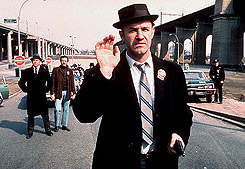

The French Connection (1971)

The French Connection (1971)

William Friedkin's classic, fact-inspired police procedural feeds off the lowdown bars in the down and dirty sections of New York, where ultra-tough, ultra-flawed cop Popeye Doyle (Gene Hackman) obsesses over breaking a multimillion dollar heroin smuggling operation spearheaded by suave Frenchman Alan Charnier, aka "Frog I" (Fernando Rey). The cat-and-mouse game escalates and grows increasingly deadly, as Doyle harasses and beats a stoolie (just for show), cavalierly risks his life (and the lives of many others), shoots an unarmed would-be assassin in the back, and generally behaves in far from heroic fashion. As the film's trailer says, Popeye Doyle is "bad news, but he's a good cop." (Some of us are not convinced of the latter.) The film's famed chase sequence through the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn and onto an elevated train remains one of the most visceral and just plain terrifying action sequences ever filmed, made all the more suspenseful by the sheer ordinariness of the urban landscape. But that's not all – and this is not easy to describe briefly – "The French Connection" just feels more like New York than 99.9 percent of the films shot there. It's like the city just seeped into the film stock.

William Friedkin's classic, fact-inspired police procedural feeds off the lowdown bars in the down and dirty sections of New York, where ultra-tough, ultra-flawed cop Popeye Doyle (Gene Hackman) obsesses over breaking a multimillion dollar heroin smuggling operation spearheaded by suave Frenchman Alan Charnier, aka "Frog I" (Fernando Rey). The cat-and-mouse game escalates and grows increasingly deadly, as Doyle harasses and beats a stoolie (just for show), cavalierly risks his life (and the lives of many others), shoots an unarmed would-be assassin in the back, and generally behaves in far from heroic fashion. As the film's trailer says, Popeye Doyle is "bad news, but he's a good cop." (Some of us are not convinced of the latter.) The film's famed chase sequence through the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn and onto an elevated train remains one of the most visceral and just plain terrifying action sequences ever filmed, made all the more suspenseful by the sheer ordinariness of the urban landscape. But that's not all – and this is not easy to describe briefly – "The French Connection" just feels more like New York than 99.9 percent of the films shot there. It's like the city just seeped into the film stock.

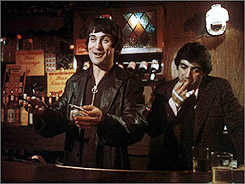

Mean Streets (1973)

Mean Streets (1973)

Martin Scorsese set the template for gritty, ethnic New York independent films – and did it better than practically anyone else – in this breakthrough tale about a young and ambitious small-time semi-hood (Harvey Keitel) caught between the wrong side of the law, the Catholic Church, and his increasingly dangerous loyalty to his loose-cannon best pal (Robert De Niro). A New York filmmaker from the get-go, Scorsese films the dive bars, bistros and celebrations of Little Italy to the beat of music by Phil Specter and the Rolling Stones with his trademark visceral gusto. He also invents a few now-common camera tricks, as he captures the language, humor and brutality of not-primarily criminal Italian-Americans. Scorsese doesn't glamorize Little Italy the way his contemporary Francis Coppola did in "The Godfather" – he does the opposite. However, his visions do not lack for beauty and color. Whether he's capturing a billiard-room brawl, a brutal assassination of an anonymous drunk played by David Carradine, or a bedroom make-out session between two lovers, we never forget that this can all only be happening in one place on earth.

Martin Scorsese set the template for gritty, ethnic New York independent films – and did it better than practically anyone else – in this breakthrough tale about a young and ambitious small-time semi-hood (Harvey Keitel) caught between the wrong side of the law, the Catholic Church, and his increasingly dangerous loyalty to his loose-cannon best pal (Robert De Niro). A New York filmmaker from the get-go, Scorsese films the dive bars, bistros and celebrations of Little Italy to the beat of music by Phil Specter and the Rolling Stones with his trademark visceral gusto. He also invents a few now-common camera tricks, as he captures the language, humor and brutality of not-primarily criminal Italian-Americans. Scorsese doesn't glamorize Little Italy the way his contemporary Francis Coppola did in "The Godfather" – he does the opposite. However, his visions do not lack for beauty and color. Whether he's capturing a billiard-room brawl, a brutal assassination of an anonymous drunk played by David Carradine, or a bedroom make-out session between two lovers, we never forget that this can all only be happening in one place on earth.

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974)

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974)

The real surprise of the original version of this violent suspense thriller – about trigger-happy, machine gun-toting bad men holding a subway car crammed with hostages – is that it's every bit as funny as it is suspenseful. That's a big part of the reason why this grimly witty production from director Joseph Sargent and writer Peter Stone feels so New York. Starring the great Walter Matthau, the film's hero is a procedurally and technically savvy anti-Dirty Harry of a transit cop, trying in his own methodical, world-weary way to prevent a bloodbath against a sea of indifferent bureaucrats and nervous politicians. And there's the odd, fatalistic poetry of the grimy side of NYC that infuses "Pelham." Lines like "We had a bomb scare in the Bronx yesterday, but it turned out to be a cantaloupe," and "Screw the goddamn passengers! What the hell did they expect for their lousy 35 cents -- to live forever?" can only be said with gusto in one city on the planet, and it sure isn't Duluth.

The real surprise of the original version of this violent suspense thriller – about trigger-happy, machine gun-toting bad men holding a subway car crammed with hostages – is that it's every bit as funny as it is suspenseful. That's a big part of the reason why this grimly witty production from director Joseph Sargent and writer Peter Stone feels so New York. Starring the great Walter Matthau, the film's hero is a procedurally and technically savvy anti-Dirty Harry of a transit cop, trying in his own methodical, world-weary way to prevent a bloodbath against a sea of indifferent bureaucrats and nervous politicians. And there's the odd, fatalistic poetry of the grimy side of NYC that infuses "Pelham." Lines like "We had a bomb scare in the Bronx yesterday, but it turned out to be a cantaloupe," and "Screw the goddamn passengers! What the hell did they expect for their lousy 35 cents -- to live forever?" can only be said with gusto in one city on the planet, and it sure isn't Duluth.

Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

While it only goes from Brooklyn to Kennedy Airport, and has the dubious distinction of being the first example of the quiet-LOUD technique that Al Pacino would ride to Oscar glory 17 years later (a pensive "I'm dying over here" one minute, a thunderous "Attica!" the next) "Dog Day Afternoon" is one of New York's finest -- a funny yet tragic tale of a rookie bank robber whose first day on the job goes impossibly wrong. Never mind the fact that the movie became the blueprint for all the botched-heist films made in its wake ("Inside Man," we love you, but well, you know), but what really establishes "Dog Day Afternoon" as a true New York movie is the love story at its core. Pacino's character has a wife and kids, yes, but his true love, and motivation for knocking off the bank, is Leon Shermer, his unstable "wife" who's desperate for sexual reassignment surgery. That, friends, is not happening in Peoria. Not in 1975.

While it only goes from Brooklyn to Kennedy Airport, and has the dubious distinction of being the first example of the quiet-LOUD technique that Al Pacino would ride to Oscar glory 17 years later (a pensive "I'm dying over here" one minute, a thunderous "Attica!" the next) "Dog Day Afternoon" is one of New York's finest -- a funny yet tragic tale of a rookie bank robber whose first day on the job goes impossibly wrong. Never mind the fact that the movie became the blueprint for all the botched-heist films made in its wake ("Inside Man," we love you, but well, you know), but what really establishes "Dog Day Afternoon" as a true New York movie is the love story at its core. Pacino's character has a wife and kids, yes, but his true love, and motivation for knocking off the bank, is Leon Shermer, his unstable "wife" who's desperate for sexual reassignment surgery. That, friends, is not happening in Peoria. Not in 1975.

Manhattan (1979)

Manhattan (1979)

Shot in stunning widescreen black-and-white by director of photography Gordon Willis, and featuring orchestral versions of tunes by George Gershwin, the more biting, poetic, and complex follow-up to Woody Allen's breakthrough "Annie Hall" has a rather bleak view of love and friendship in the late 20th century. It is, however, absolutely smitten with Allen's hometown. It begins with a comedy-inflected tone poem salute to the city as we hear Allen attempting to start what promises to be a ridiculously pretentious novel: "He was as tough and romantic as the city he loved. Beneath his black-rimmed glasses was the coiled sexual power of a jungle cat." In light of later events in Allen's own life – and even not in light of them – many today are likely to feel slightly squirmy about the film's portrayal of a relationship between the 42-year-old Allen and a 17-year-old high school student (Mariel Hemingway). However, its iconic scene featuring Allen and Diane Keaton sitting beneath the 59th Street bridge is one of the most enduring images in American cinema for a reason. It embodies the beauty and poetry of a city that still represents the hope of America.

Shot in stunning widescreen black-and-white by director of photography Gordon Willis, and featuring orchestral versions of tunes by George Gershwin, the more biting, poetic, and complex follow-up to Woody Allen's breakthrough "Annie Hall" has a rather bleak view of love and friendship in the late 20th century. It is, however, absolutely smitten with Allen's hometown. It begins with a comedy-inflected tone poem salute to the city as we hear Allen attempting to start what promises to be a ridiculously pretentious novel: "He was as tough and romantic as the city he loved. Beneath his black-rimmed glasses was the coiled sexual power of a jungle cat." In light of later events in Allen's own life – and even not in light of them – many today are likely to feel slightly squirmy about the film's portrayal of a relationship between the 42-year-old Allen and a 17-year-old high school student (Mariel Hemingway). However, its iconic scene featuring Allen and Diane Keaton sitting beneath the 59th Street bridge is one of the most enduring images in American cinema for a reason. It embodies the beauty and poetry of a city that still represents the hope of America.

The Warriors (1979)

The Warriors (1979)

John McClane had a hell of a time trying to get from the Bronx to lower Manhattan, and all he had to deal with was traffic. Imagine, then, what the members of the street gang the Warriors were up against once they were wrongly fingered for the death of the leader of rival gang the Gramercy Riffs – at a peace accord, no less – and must avoid both the police and the other gangs as they escape the Bronx on foot en route to their home turf of Coney Island. The idea of turning New York into a place that's too dangerous for its own criminals was not a new one – the book on which the movie was based came out in 1965, and that book was based on the works of 400 B.C.-era Greek soldier Xenophon. But it was rather timely: the city had just undergone blackouts, riots and mass looting two years earlier, so turning predator into prey appealed to both sinners and saints -- eventually. The movie made $22 million at the box office, but slowly built a cult following, and enjoys a 93 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes today. Can you dig it?

John McClane had a hell of a time trying to get from the Bronx to lower Manhattan, and all he had to deal with was traffic. Imagine, then, what the members of the street gang the Warriors were up against once they were wrongly fingered for the death of the leader of rival gang the Gramercy Riffs – at a peace accord, no less – and must avoid both the police and the other gangs as they escape the Bronx on foot en route to their home turf of Coney Island. The idea of turning New York into a place that's too dangerous for its own criminals was not a new one – the book on which the movie was based came out in 1965, and that book was based on the works of 400 B.C.-era Greek soldier Xenophon. But it was rather timely: the city had just undergone blackouts, riots and mass looting two years earlier, so turning predator into prey appealed to both sinners and saints -- eventually. The movie made $22 million at the box office, but slowly built a cult following, and enjoys a 93 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes today. Can you dig it?

Escape from New York (1981)

Escape from New York (1981)

All right, so John Carpenter's dystopian vision of the United States circa 1997 didn't quite come to pass, but turning the destination city of New York into a maximum-security prison is still a genius move, with bonus points for casting the bad mother-shut-your-mouth Isaac Hayes as the unofficial Duke of New York. Several movies have highlighted the seedier sides of New York, but no one had dreamt of making its inhabitants nothing but the worst of humanity. That idea clearly appealed to a lot of people, because the movie made almost 10 times its budget worldwide upon its original release. It also gave birth to one of Hollywood's most legendary anti-heroes, the not-dead and not-taller Snake Plissken. As he attempts to rescue the president of the United States after a hijacking downs Air Force One in Manhattan, Snake must survive a twisted decathlon of sorts, using a glider to land on the World Trade Center towers, being forced to fight a man twice his size (and winning), and running across a landmine-riddled 69th Street Bridge. Some might view "Escape from New York" as a commentary about our violent society. We think those people are pussies.

All right, so John Carpenter's dystopian vision of the United States circa 1997 didn't quite come to pass, but turning the destination city of New York into a maximum-security prison is still a genius move, with bonus points for casting the bad mother-shut-your-mouth Isaac Hayes as the unofficial Duke of New York. Several movies have highlighted the seedier sides of New York, but no one had dreamt of making its inhabitants nothing but the worst of humanity. That idea clearly appealed to a lot of people, because the movie made almost 10 times its budget worldwide upon its original release. It also gave birth to one of Hollywood's most legendary anti-heroes, the not-dead and not-taller Snake Plissken. As he attempts to rescue the president of the United States after a hijacking downs Air Force One in Manhattan, Snake must survive a twisted decathlon of sorts, using a glider to land on the World Trade Center towers, being forced to fight a man twice his size (and winning), and running across a landmine-riddled 69th Street Bridge. Some might view "Escape from New York" as a commentary about our violent society. We think those people are pussies.

Ghostbusters (1984)

Ghostbusters (1984)

Given that the first five minutes of "Ghostbusters" offers both a sweeping crane shot in front of the New York Public Library, and a stroll down the hallowed halls of Columbia University, it's clear that director Ivan Reitman and cinematographer Lazlo Kovacs wanted to make New York City as much of a character in the film as Drs. Stanz, Spengler and Venkman. And so they did: not only do we see the ‘Busters bopping around NYC behind the wheel of the former hearse known as ECTO-1, but they quickly become the toast of the city – which is ironic, given that the city almost ended up being toast, thanks to misguided EPA dweeb Walter Peck releasing all of the ghosts that the guys had captured. Reitman couldn't make all of his dreams come true: he envisioned the hotel haunting taking place at the Algonquin, but he had to make do with filming at the Biltmore and calling it the Sedgewick. But "Ghostbusters" still ended up being pretty darned New York-y. Dana Barrett's apartment at 55 Central Park West has become a landmark even though the inter-dimensional rift has closed, and it's now officially impossible to drive past Hook and Ladder Company #8 (otherwise known as the ‘Busters' headquarters), without demanding to know, "Who you gonna call?"

Given that the first five minutes of "Ghostbusters" offers both a sweeping crane shot in front of the New York Public Library, and a stroll down the hallowed halls of Columbia University, it's clear that director Ivan Reitman and cinematographer Lazlo Kovacs wanted to make New York City as much of a character in the film as Drs. Stanz, Spengler and Venkman. And so they did: not only do we see the ‘Busters bopping around NYC behind the wheel of the former hearse known as ECTO-1, but they quickly become the toast of the city – which is ironic, given that the city almost ended up being toast, thanks to misguided EPA dweeb Walter Peck releasing all of the ghosts that the guys had captured. Reitman couldn't make all of his dreams come true: he envisioned the hotel haunting taking place at the Algonquin, but he had to make do with filming at the Biltmore and calling it the Sedgewick. But "Ghostbusters" still ended up being pretty darned New York-y. Dana Barrett's apartment at 55 Central Park West has become a landmark even though the inter-dimensional rift has closed, and it's now officially impossible to drive past Hook and Ladder Company #8 (otherwise known as the ‘Busters' headquarters), without demanding to know, "Who you gonna call?"

Moonstruck (1987)

Moonstruck (1987)

One thing that strikes a visitor to New York from more overtly polite places is the emotionalism of the city. Some may call it rudeness, but we call it giving a damn. Never has 1980s New York seemed so romantic, oddly serene, and comically melodramatic as it does in writer John Patrick Shanley and director Norman Jewison's Oscar-winning neo-Shakespearian comedy of passion, manners and hilariously over-the-top emotions. Set primarily in a far less crime-ridden version of Little Italy than we're used to from other movies, the comedy is set in motion when prematurely graying, superstitious thirtysomething widow Loretta Castorini (Cher) meets Ronny Cammareri (Nicolas Cage, in a career-making performance) the sensitive and volcanically emotional estranged younger brother of her not so impressive fiancé (Danny Aiello). The comedy flows from the operatically excessive emotions of characters in a world where emotion and irrationality rules. It's terribly funny and sometimes kind of moving because it rings true. Say what you like of the ethnic residents of New York and its boroughs – they care a lot. Maybe a little too much sometimes, but whadyagonnado?

One thing that strikes a visitor to New York from more overtly polite places is the emotionalism of the city. Some may call it rudeness, but we call it giving a damn. Never has 1980s New York seemed so romantic, oddly serene, and comically melodramatic as it does in writer John Patrick Shanley and director Norman Jewison's Oscar-winning neo-Shakespearian comedy of passion, manners and hilariously over-the-top emotions. Set primarily in a far less crime-ridden version of Little Italy than we're used to from other movies, the comedy is set in motion when prematurely graying, superstitious thirtysomething widow Loretta Castorini (Cher) meets Ronny Cammareri (Nicolas Cage, in a career-making performance) the sensitive and volcanically emotional estranged younger brother of her not so impressive fiancé (Danny Aiello). The comedy flows from the operatically excessive emotions of characters in a world where emotion and irrationality rules. It's terribly funny and sometimes kind of moving because it rings true. Say what you like of the ethnic residents of New York and its boroughs – they care a lot. Maybe a little too much sometimes, but whadyagonnado?

Do the Right Thing (1989)

Do the Right Thing (1989)

During the mid-to-late ‘80s, New York's boroughs became synonymous with racial tension. (L.A. got its turn in 1992.) Whether you think it's a classic of thoughtful American cinema or an arguably racist apologia for urban violence, Spike Lee's anatomy of a neighborhood race riot fueled by hate, heat and misunderstandings dealt with the issue far more forcefully than any major film before or since. In all the politically and ethnically charged controversy, however, the poetic side of Lee's signature film still tends to get lost. Like any great city, New York is comprised of great communities. Brooklyn's Bedford-Stuyvesant, as captured by cinematographer Ernest Dickerson, is a colorful, exciting and joyful place, full of light, candy-colored buildings and bold, playful imagery. "Do the Right Thing" does an even better job of capturing the people of Bed-Stuy as they gather at Sal's Pizzeria, cool themselves around open fire hydrants, and just try to get through the day. True, many of its characters resort to ethnic name-calling and worse – it's an NYC tradition – but Lee's best film never lets us forget that people are much more than their prejudices and hatreds.

During the mid-to-late ‘80s, New York's boroughs became synonymous with racial tension. (L.A. got its turn in 1992.) Whether you think it's a classic of thoughtful American cinema or an arguably racist apologia for urban violence, Spike Lee's anatomy of a neighborhood race riot fueled by hate, heat and misunderstandings dealt with the issue far more forcefully than any major film before or since. In all the politically and ethnically charged controversy, however, the poetic side of Lee's signature film still tends to get lost. Like any great city, New York is comprised of great communities. Brooklyn's Bedford-Stuyvesant, as captured by cinematographer Ernest Dickerson, is a colorful, exciting and joyful place, full of light, candy-colored buildings and bold, playful imagery. "Do the Right Thing" does an even better job of capturing the people of Bed-Stuy as they gather at Sal's Pizzeria, cool themselves around open fire hydrants, and just try to get through the day. True, many of its characters resort to ethnic name-calling and worse – it's an NYC tradition – but Lee's best film never lets us forget that people are much more than their prejudices and hatreds.

You can follow us on Twitter and Facebook for content updates. Also, sign up for our email list for weekly updates and check us out on Google+ as well.